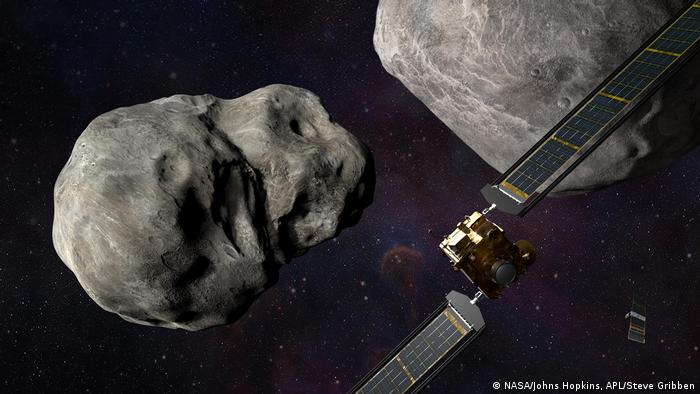

After climate change, the next threat in the next hundred years is asteroids. But NASA has a plan: a mission called DART.

DW : There are asteroids of different sizes, structures and materials. Some are basically metal balls and some are "gravel pits". But let's focus on size first: the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) Mission is heading toward an asteroid pair, Didymos, and its moon, Didymoon. It is a binary near-Earth asteroid. Didymos is about 780 meters in diameter and Didymoon, 160 meters wide. But you think that smaller asteroids, like Didymoon, pose a greater threat to life on Earth. Why?

Thomas Zurbuchen : Yes, it is true. Smaller asteroids are a much bigger threat to Earth and this can be seen if we look at the "crater history" of the moon or our own environment. We've had a similar asteroid bombardment for millions of years, but it just can't be appreciated, because we have very active geology on Earth.

We know some [more important] facts, like the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs. It was 10 kilometers in size. This type of asteroid changes the entire planet, or life on it, but today we do not know of any asteroid of those dimensions. If a 160-meter asteroid falls on a city, it will be a bad day for that city, but it will not change the entire planet.

Wait, let's back up a bit. If an asteroid lands in a city, "it's a bad day for that city." What's a bad day for a city when an asteroid hits it?

It depends on the size of the crater. As I said, the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs was 10 km in diameter, but the crater it left was 100 or 200 km, 10 times the size (of the asteroid) or more. So a 160-meter asteroid would leave a crater of more than a kilometer.

So what prevents us from detecting these asteroids?

Well, we are working on it. There are observatories around the Earth, observing the sky at night. Two of the most productive telescopes are in Hawaii and each night they observe two to three new asteroids.

But we also need to go into space to get to 100 percent. We are starting a mission at NASA called the NEO surveyor, or Near Earth Orbit Surveyor, and that is precisely what it will do. It will be released in a few years.

But right now they are starting DART. Tell us about this idea of causing a "kinetic impact deflection" at Didymoon at a speed of 6.6 km / s. That, as I understand it, will deflect the asteroid enough to change its orbit in a couple of minutes. Would it be enough to prevent an asteroid from hitting Earth?

As is often the case, it depends on a few variables. First, it depends on how far in advance we observed the asteroid before impact. Second, it depends on the mass of the asteroid. We want to change its speed, and the relationship between the mass of the asteroid and the spacecraft is important. And third, the asteroid's orbit is important: you want a head-on collision to use the asteroid's energy. So it all depends. But this is precisely why we are testing this technology, because all those variables are unknown at the moment.

And at what distance?

Many of these objects are at the distance between the Sun and the Earth (editor's note: 149,600,000 km) or more. It could be from the orbit of Mars or beyond and up to Venus. It is all that range of possibilities.

And what role do Europeans play with the launch of their part of the mission, the HERA probe, in 2024?

DART will impact the asteroid and create a crater. ESA's HERA probe will then investigate the crater and determine why our impact created the motion and the crater it generated.

How beneficial is planetary defense support? I mean, we are dealing with climate change on a scale smaller than decades as opposed to centuries of asteroids. Do you have the support you need or are there people who say, "Let's see if we have a planet to save in a hundred years" before we figure out how to save it from asteroids?

At NASA, we believe that we should support research on various time scales. Think about these numbers: there is a proposed budget for Earth sciences, which is the focus of the climate crisis, 2.2 billion euros per year. The planetary defense budget at the moment is about 1.2 billion euros a year. But if a threat arises, we will increase that budget.

I have kids. I will do everything I can to make sure the Earth is in good condition a hundred years from now. And that is why we are committed to climate science, but at the same time we want to look at the threats that are less imminent and build the tools to have them in case the threat does arise.

Dr. Thomas Zurbuchen is chief science officer in NASA's Science Mission Directorate.

Interview by Zulfikar Abbany

(rmr / ms)

---------------------------

DW : Hay asteroides de diferentes tamaños, estructuras y materiales. Algunos son básicamente bolas de metal y otros son "pozos de grava". Pero centrémonos primero en el tamaño: la Misión Doble Prueba de Redirección de Asteroides (DART) se dirige hacia un pareja de asteroides, Didymos y su luna, Didymoon. Se trata de un asteroide binario cercano a la Tierra. Didymos tiene unos 780 metros de diámetro y Didymoon, 160 metros de ancho. Pero usted cree que asteroides más pequeños, como Didymoon, suponen una mayor amenaza para la vida en la Tierra. ¿Por qué?

Thomas Zurbuchen: Sí, es cierto. Los asteroides más pequeños son una amenaza mucho mayor para la Tierra y esto se puede comprobar si miramos la "historia de los cráteres" de la luna o la de nuestro propio entorno. Hemos tenido un bombardeo similar de asteroides durante millones de años, pero simplemente no se puede apreciar, porque tenemos una geología muy activa en la Tierra.

Conocemos algunos hechos [más importantes], como el asteroide que acabó con los dinosaurios. Tenía 10 kilómetros de tamaño. Ese tipo de asteroide cambia todo el planeta, o la vida en él, pero hoy no conocemos ningún asteroide de esas dimensiones. Si un asteroide de 160 metros cae sobre una ciudad, será un mal día para esa ciudad, pero no cambiará todo el planeta.

Espere, retrocedamos un poco. Si un asteroide aterriza en una ciudad, "es un mal día para esa ciudad". ¿Qué es un mal día para una ciudad cuando un asteroide choca contra ella?

Depende del tamaño del cráter. Como ya dije, el asteroide que acabó con los dinosaurios tenía 10 km de diámetro, pero el cráter que dejó tenía 100 o 200 km, 10 veces el tamaño (del asteroide) o más. Entonces, un asteroide de 160 metros dejaría un cráter de más de un kilómetro.

Entonces, ¿qué nos impide detectar estos asteroides?

Bueno, estamos trabajando en ello. Hay observatorios alrededor de la Tierra, observando el cielo por la noche. Dos de los telescopios más productivos se encuentran en Hawái y cada noche observan de dos a tres nuevos asteroides.

Pero también necesitamos ir al espacio para llegar al 100 por cien. Estamos comenzando una misión en la NASA llamada NEO surveyor, o Near Earth Orbit Surveyor, y eso es lo que precisamente hará. Se lanzará en unos años.

Pero ahora mismo están iniciando DART. Cuéntenos acerca de esta idea de originar una "desviación de impacto cinético" en Didymoon a una velocidad de 6,6 km/s. Eso, según tengo entendido, desviará al asteroide lo suficiente para cambiar su órbita en un par de minutos. ¿Sería suficiente para evitar que un asteroide golpeara la Tierra?

Como suele ocurrir, depende de algunas variables. Primero, depende de la antelación con la que observáramos el asteroide antes del impacto. En segundo lugar, depende de la masa del asteroide. Queremos cambiar su velocidad, y la relación entre la masa del asteroide y la nave espacial es importante. Y tercero, la órbita del asteroide es importante: lo deseable es lograr una colisión frontal para usar la energía del asteroide. Entonces, todo depende. Pero esta es precisamente la razón por la que estamos probando esta tecnología, porque todas esas variables son desconocidas en estos momentos.

¿Y a qué distancia?

Muchos de estos objetos se encuentran a la distancia que hay entre el Sol y la Tierra (nota del editor: 149.600.000 km) o más. Podría ser desde la órbita de Marte o más allá y hasta Venus. Es todo ese abanico de posibilidades.

¿Y qué papel desempeñan los europeos con el lanzamiento de su parte de la misión, la sonda HERA, en 2024?

DART impactará el asteroide y creará un cráter. La sonda HERA de la ESA investigará luego el cráter y determinará por qué nuestro impacto creó el movimiento y el cráter que generó.

¿Qué tan beneficioso es el apoyo a la defensa planetaria? Quiero decir, nos enfrentamos al cambio climático en una escala menor de décadas a diferencia de los siglos de los asteroides. ¿Tiene el apoyo que necesita o hay gente que dice: "Veamos si tenemos un planeta que salvar en cien años" antes de que averigüemos cómo salvarlo de los asteroides?

En la NASA, creemos que debemos apoyar la investigación en varias escalas de tiempo. Piense en estos números: hay un presupuesto propuesto para las ciencias de la Tierra, que es el foco de la crisis climática, 2.200 millones de euros por año. El presupuesto de defensa planetaria en este momento es de unos 1.200 millones de euros anuales Pero, si surge una amenaza, aumentaremos ese presupuesto.

Tengo hijos. Haré todo lo que pueda para asegurarme de que la Tierra esté en buenas condiciones dentro cien años. Y es por eso que estamos comprometidos con la ciencia del clima, pero, al mismo tiempo, queremos observar las amenazas que son menos inminentes y construir las herramientas para tenerlas en caso de que surja la amenaza.

El Dr. Thomas Zurbuchen es director científico en la Dirección de Misiones Científicas de la NASA.

Entrevista realizada por Zulfikar Abbany

(rmr/ms)

Source consulted /www.dw.com/

Read less